Can the Trypillia show us the way forward?

6000 year old knowledge can help us get out of the current mess.

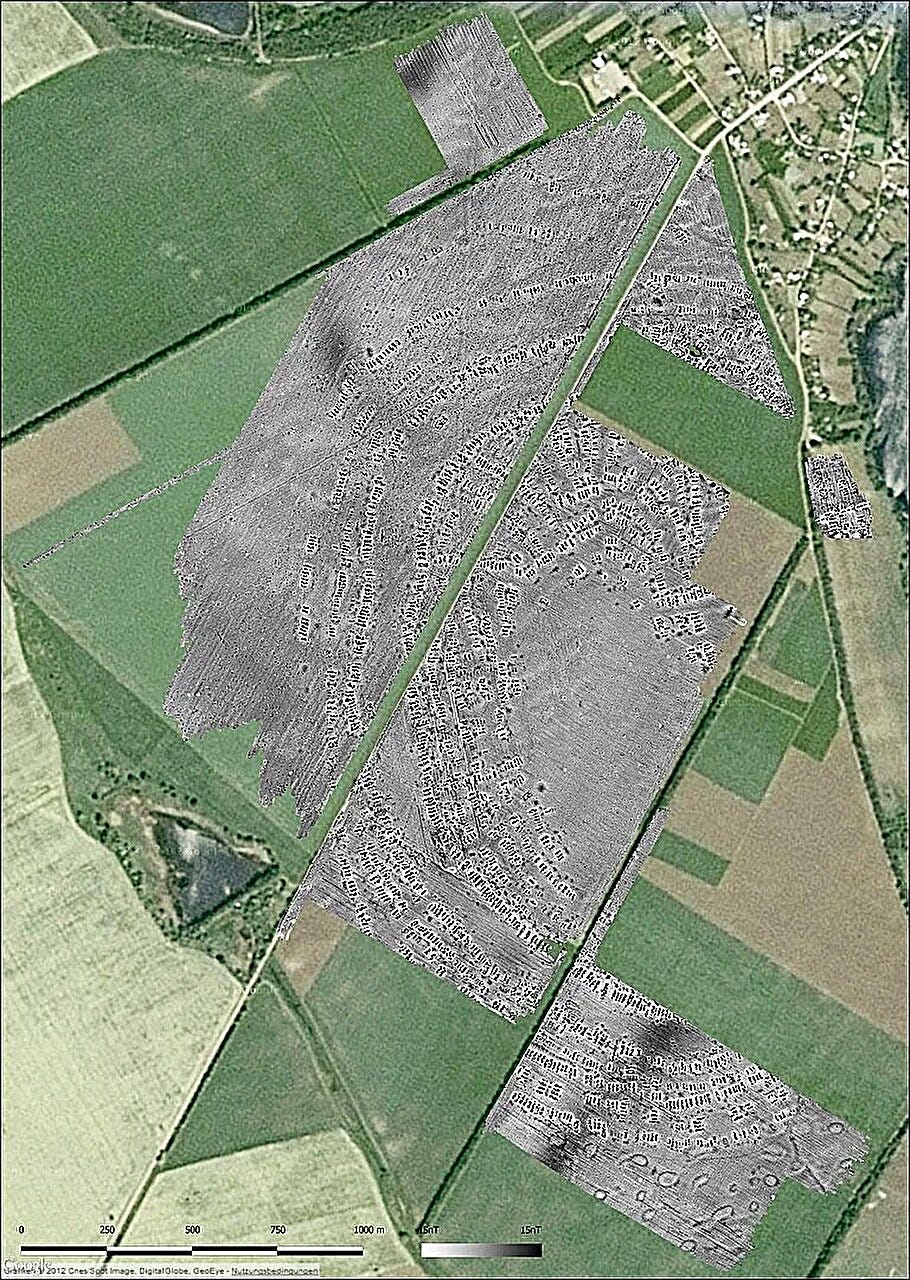

I am, as you will have guessed, talking about the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture that built what are considered to be the oldest cities in Europe. These settlements grew up around 6000 years ago and covered areas up to 320 hectares in size and housed around 15,000 citizens.

Why would I suggest that we can learn from this civilisation? For several reasons.

Disease

Earlier big settlements, such as Çatalhöyük seem to have been abandoned because of disease. Çatalhöyük, widely considered to be the world’s oldest farming village grew up about 9000 years ago and was then abandoned 6000 years ago. The houses in this mega-village were so closely packed together that people got into them through a trapdoor in the roof. The inhabitants kept their homes clean, they seem to have regularly replastered the walls and they swept the floors. They lived in a high-density setting and their domestic animals were packed in with them. This led to big zoonotic disease problems from things like influenza, salmonella, malaria and tuberculosis.

Being sedentary, packed together and in close proximity to the animals meant that these people suffered more from disease than their hunter-gatherer ancestors. In fact, the farmer’s immune systems changed and adapted. The Covid pandemic showed how our immune systems can overreact to a new type of infection. The immune system response can be so strong that it kills the host. The immune systems of the early farmers adapted to produce fewer cytokines (interleukin and interferon) which meant a less powerful inflammation. This meant that fewer died from their body’s response to the infection. They still got ill but survived more often than their hunter-gatherer ancestors would have, had the latter been living in the same conditions.

It seems as if that living in a built environment that continually made people ill meant that eventually the mega-village was abandoned.

The Cucuteni-Trypillian peoples seem to have learnt from this experience and their cities were built in a completely different way. They built two-storey wooden houses that were spaced apart, these were organised in wedge-shaped neighbourhoods. Each neighbourhood had its own meeting house. The inhabitants regularly burnt houses and even neighbourhoods, up to 2/3rds of the total area sometimes. Some researchers maintain that this was probably done for ritual reasons, it’s more likely that it was done for disease control. An infested area would be burnt and rebuilt.

This is fascinating as it means that we had figured out organise to build cities to reduce disease transmission, and we did this 6000 years ago. Well done us, it’s a shame that we then forgot about this strategy and, millennia later, built towns and cities that actively encouraged the spread of disease.

Food

The Cucuteni-Trypillian people grew club wheat, oats, commun (Triticum compactum which is adapted to drier conditions) millet, rye, barley, and hemp. They also cultivated a lot of peas, they had orchards producing apricots, cherry plums and grapes. The peas, in particular, helped these people have a diet that was balanced in terms of amino acids.

They ran cattle, pigs, goats and sheep in paddocked areas. The manure was used to fertilise the cropping areas. The residual crop waste, pea straw, for example, was used as an animal feed supplement.

Whilst they had these domesticated animals and also hunted and fished they were predominantly vegetarian. This reduced the burden of raising a lot of animals for meat and also reduced the spread of diseases through contaminated meat.

A quick look at the old Saxons

Many of us were brought up thinking that the Saxon Kings of the time ate a lot of meat produced by subservient peasants. The peasants were forced to hand over meat and other crops as part of a food-rent system called feorm.

More modern research has shown this picture to be false. The King’s diet wasn’t particularly different to that of the peasants. The peasants were free and feorm actually meant ‘a feast’. At this time people mainly ate grains (in the form of bread and porridge), vegetables, fruit and nuts and a bit of meat. Kings and peasants the same. Every so often the free peasantry would organise a big knees-up, invite the King, and then they all got their heads around a lot of meat. This is fascinating because the massive increase in meat eating we have seen over the last few decades is seen as being ‘aspirational’. People aspire to what they perceive as being a wealthy person’s diet. History is showing us that the Kings of old didn’t feast on meat all the time. This came in later when the free peasantry lost their liberty under the Feudal system.

So the Cucuteni-Trypillian cities were self-sufficient in food, the sophisticated organisation of the waste cycling maintained fertility and provided a balanced, indeed very healthy diet.

Cucuteni-Trypillian economy and politics

It seems that, and this is different to the hunter-gatherer societies that have been studied, gender played a role in who did what. The women seem to have been the heads of the households and did most of the farming. The men hunted, fished and looked after the domesticated animals.

Each neighbourhood had its meeting-house where the locals would gather to eat and organise their lives. The whole thing seems to have been equitable, but this changed. The culture lasted 500 years and we currently believe that it collapsed when the political organisation became more centralised and social inequality increased.

Faced with this inequality and the appropriation of social control by an elite people simply moved away. They went off and founded smaller settlements elsewhere.

Social control by an elite political class is the norm in today’s world. As is increasing inequality and social injustice. Perhaps we can learn from the Cucuteni-Trypillian people?

“Not possible,” I hear people say, “there’s no space to move to.”

This isn’t the case. Across the world, an area, almost half the size of Australia, has been abandoned. Part of this is agricultural land, in the US alone an estimated 30 million hectares of farmland have been abandoned since the 1980’s. The rest is pastures, forestry areas, mines, factories, and human settlements. There is even a Wikipedia page dedicated to abandoned villages, that said a number of them could not be re-inhabited for a variety of reasons.

There are even more villages that are slowly dying as people leave and the remaining people age. Most of us have heard about the 1€ house initiative in Italy, here’s a map of them.

The UN and other organisations project increasing urbanisation, with more and more of the global population living in cities. These are, however, projections based on recent historical data. A projection doesn’t mean that this will be the case. Another possibility is that, faced with the increasingly intolerable urban living conditions. Faced with increasing inequity and inequality we will de-urbanise and recolonise the abandoned land and villages. This is already happening in some countries, under the radar and un-mediatised, but happening all the same. It’s time for more of us to do the same. We can design and build sustainable and abundant smaller-scale human settlements, we did it 6000 years ago, we can do it again today.

For those who will protest that we need to rewild areas to fight against global warming, I would maintain that we can do both, further support for this idea can be found in this research. Any Permaculture-designed area has a wild zone. The small-scale agriculture would be based on agro-forestry and sylvo-agro-pasturalism. This means trees with crops. Trees stock carbon and when used as timber to build houses the carbon is locked away for the lifetime of the house.

With our current medical knowledge, we can avoid having to burn houses down. An improved diet would mean that we are healthier and less prone to the diseases associated with modern living. We now have access to a lot of crops that the Cucuteni-Trypillian people didn’t know about, this means that our local agricultural systems can be even more diverse and sophisticated.

Let’s get on with it!

References

http://antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/chapman339/

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsif.2024.0313

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2312962120

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adf1099

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ad2d12

Another great article, thanks. You say "Any Permaculture-designed area has a wild zone" which is one of it's great qualities, though what makes a really good wildlife habitat is continuity - to have multiple zone 5s linked to corridoors and larger refuges, rather than islands. That's more of a challenge in an urban/suburban setting, though it too has precedents e.g. the fingers of wild woods seeping down river valley systems from the moors, almost as far as central Sheffield