Less air pollution means more soil carbon loss, cod, strange attractors and the butterfly effect

Air pollution, in general, is bad for our health, the Nitrous oxides produced by vehicles, especially heavy-goods lorries, cause lung irritation and weaken our defenses against diseases such as pneumonia and influenza. It’s a greenhouse gas and as such it’s much more potent than methane and carbon dioxide. In the atmosphere it also damages the ozone layer, at ground level it combines and forms ozone.

Because of all this measures have been enforced over the last few decades to reduce emissions from vehicles. Around 200 million tonnes of reactive nitrogen in the form of ammonia is still lost to the atmosphere from the ammonium nitrate used as a crop fertiliser. Not enough is being done to reduce this environmental burden.

So, nitrogen, when it goes up is a powerful greenhouse gas, when it comes down it reduces microbial decomposition of soil organic matter and reduces global warming.

It’s those rascal bacteria again. There is a bunch of them that break down soil organic matter and this releases carbon to the atmosphere which accelerates global heating. When the leaf litter or soil has anthropogenic Nitrogen deposed on it the microbial activity that I just mentioned is reduced. This means that more carbon is stocked in the soil.

The measures that have been put into place to reduce vehicle emissions have had the unintended consequence of changing microbial activity. This means that more carbon is being lost from soils and adding to global warming. The authors point out that this may be a transitional phase as the ecosystem adjusts to the Human induced impact.

This is another example of natural systems adjusting and adapting to our activities and their consequences. We tend to think that, when our impact is removed or reduced, that things will go back to how they were. This isn’t always the case, in fact this would be the exceptional. Imagine a metal ball hanging on a string, push the ball and it will always settle back to it’s point attractor, hanging straight down. If we then surround the ball with a circle of individual magnets and then give the ball a push it becomes hard it not impossible to predict where the ball will end up. Each magnet is a new attractor and the ball will end up stuck to one of them, which one? We can’t tell.

The first image, the pendulum on it’s own is how many people would judge how an ecosystem works. Remove the stress factors, the pollution, people, synthetic chemicals or whatever and the ecosystem will return to it’s original state. The second image, the one with the magnets, is a more realistic picture. If we change the parameters of a system then we can’t predict what will happen. It’s deterministic chaos.

Take North Atlantic cod as an example. A simple idea would be that if we reduce how many are fished then the population will rebound and all will be OK. In fact these fish stocks haven’t rebounded as was forecast. It worked OK for plaice and hake but not for cod. It seems likely that they were fished beyond an ecological tipping point. Their numbers were so reduced that the ecosystem in which they thrived was changed and tipped into another attractor state in which cod can’t bounce back. Their ecological niche has, in many ways, disappeared. In Ecology we call this a critical transition, due to stress the ecosystem has bifurcated to another form.

The above example, and Blue whales are another, is a form of ratchet effect. Once things have gone in one direction it’s difficult to go back. We can also see hysteresis in these systems, it takes much more effort to restore a system then it did to break it. If we completely stopped fishing cod and they were no longer caught as a by-catch then maybe their numbers would eventually grow, limiting fishing hasn’t worked, it’s not enough.

We have to better understand that ‘nature’ isn’t perfect. Evolution is haphazard, the idea that lifeforms evolve in a linear way from simple to complex doesn’t reflect what really happens. Some complex animals and plants go extinct, some revert to less complex forms, there isn’t an ideal ‘direction’ nor an end goal.

One of the problems is that the new stable states that ecosystems find are not necessarily ideal for us as a species. They may be less productive, more difficult to farm, less stable. They say that ‘nature abhors a vacuum’, in ecological terms removing large numbers of an animal or plant leaves ecological niches available to other animals or plants. Ones which are more adapted to the new ecological parameters of said niche.

The Blue whales, hunted to near extinction, are an example of a negative feedback loop. Their bodily wastes fertilise the ocean and this fertility is used by the krill, fewer wastes means fewer krill and so less food for the whales.

This kind of things should act as a warning for us, one which we continue to ignore. Our activities have consequences and these impact the biosphere in ways we don’t fully understand. It’s important that we move beyond simplistic and linear views of ‘nature’, things don’t work like that. The so-called ‘butterfly effect’ should be front and foremost in our minds. Small changes to dynamical systems can be amplified through such systems to become big changes. All the living systems around us are dynamical and non-linear. They are made up of dissipative structures which are thermodynamically open system operating far from thermodynamic equilibrium, they exchange energy, matter, and information with the external environment. They have a self-organising capacity, Prigogine‘s “order out of chaos”.

These systems can be robust and resilient to shocks, they rebound. If the stressors increase or simply continue then the system itself can bifurcate to become something else which has it’s own dynamical stability. This can be as robust as the first system. Natural systems are dissimilar to the pretty paintings of ‘nature’ that we see in art galleries and we would do well to remember this.

If we wish to encourage systems to re-establish then we would do well to bear in mind the butterfly effect. What is the least we can do to have the most effect? This is a Permaculture principle.

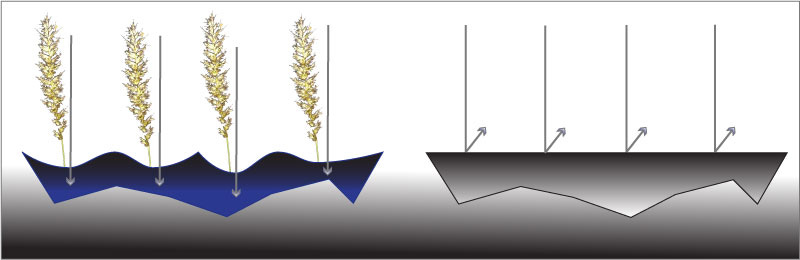

An example of this approach is the land imprinter, metal rollers with angled steel welded on. When rolled over a surface it leaves V shaped indentations which reduce run-off and accumulate water, wind driven organic debris and provide protection to young plants. Land imprinters have been used to ‘plant’ and regenerate 20,000 hectares of prairie land in Arizona.

Using beavers or beaver dam like structures to mitigate downstream flooding is another example. Let the beavers do their work and “It helps to enhance habitat diversity for river insects and animals, trap pollutants, and enhance the supply of sediment to the floodplain.”

These butterfly effect approaches tend to work well and are highly cost effective. The ratchet and hysteresis principles mean that we need a huge number of these projects if we wish to shift ecosystems from reduced states to complex ones. We also need to bear in mind, as I have mentioned that the outcome may not be identical to the system that existed before the destruction. It will also take time before they reach a climax phase with a maximum diversity of species, ecological niches and interconnections.