Reclaiming Permaculture

and putting it back in its proper place

Bill Mollison was the person who inspired my generation of Permaculture designers. His major book, A Designer’s Manual, is frankly amazing. His incredible range of knowledge and capacity to organise it all into a coherent design and engineering approach shook us up. He pioneered a way for us to move from fighting against to designing for. From reaction to action. As then, so today, there were movements of activists fighting against the military-industrial complex and its ecologically and socially destructive projects. Projects would be stopped only to be restarted a few years later, advances would be made only to be lost shortly afterwards. Burnout and suicides were common among these activists. People were struggling ‘against’, but there were few real ideas about what we could replace them with. For example, in London, there were protests against cars, which is a good thing, but the activists had no strategic plan about how to reorganise the city so that cars were redundant and not needed.

The Designers Manual showed us how we could redesign our socioeconomic, agricultural systems and replace them with ones that work better. It gave us a design and engineering discipline that could be used as a tool for real social and economic change.

Over the following years, increasing numbers of people got involved in this movement. We also saw Permaculture being reduced to gardening. We saw the integrated design and engineering discipline being usurped by people who presented it as a bunch of gardening techniques. Some amongst us accused these people of being industrial moles and collaborators, which was perhaps a bit extreme.

Mollison once said that it was anger that motivated him. This resonated strongly with us; we were angry too. Furious that poverty, inequality, shoddy housing, and environmental destruction continued even in the late 20th century. We saw it as an obscenity that had to stop. Permaculture showed us how we could redesign and rebuild. It gave, and gives us, a way to stop the stupidities of the military-industrial complex, not by fighting against, but by reconstructing our systems to make them obsolete. We can design and restructure agricultural systems in a way that means they don’t need all the toxic synthetic molecules produced by the chemical industry. We can redesign and rebuild our local communities in such a way that private cars and their pollution are scarcely needed.

Permaculture gives us a way to replace the stick with an organic, locally produced carrot. Instead of bombarding people with bad news and trying to guilt-trip them into changing their ways, we can attract them to a different way of living.

Mollison came up with a coherent system of principles:

which help us design and also view things from a different point of view. ‘Make the least change for the greatest effect,’ for example. Instead of blindly throwing time, labour, and money at something we wish to transition, we analyse the system. We try and find balance points in the system that can be leveraged to provoke positive cascade effects. We make small changes that amplify through the system to transition it to a new, dynamically stable state. A farming or market gardening example would be delimiting an area as a wild zone (zone 5 in Permaculture design parlance). This area becomes increasingly ecologically complex, and the predators of the crop ‘pests’ in the production areas are now in abundance and right next to the crops.

The above principle is pretty well known; this one can be found in the same book and is much less talked about and flies in the face of the idea that Permaculture is about gardening:

Policy of Responsibility

A beneficial authority returns function and responsibility to life and people. Successful design creates self-managed systems.

All the Permaculture principles merit deep study, this one especially so. ‘A beneficial authority’ may be an oxymoron for some, it can be argued that any ‘authority’ is by its nature non-beneficial. What Mollison is proposing is that our current political, governance, and decision-making systems are inefficient, detached from people and their reality, and have led us straight into our current mess. It’s difficult to counter this argument.

The clue to what Mollison means by ‘a beneficial authority’ lies in the second part of the principle, ‘returns function and responsibility to life and people’. This means that the primary mission of the people inside the ‘beneficial authority’ is to dismantle the authority structure. Say, for example, said group of people manages to get elected to and have a majority in a government. Their mission will be to restructure it in such a way that the responsibility for decision-making and governance in general goes to the people and away from the political elite. They would probably use this Permaculture approach:

Keep what works well; if it ain’t broke, they don’t need to fix it.

Reorganise, restructure that which works less well but is worth keeping going.

Stop and remove anything that goes against the Permaculture ethics. If it doesn’t take care of people and the biosphere, it must be eliminated.

This group of intrepid political pioneers will undoubtedly, and for the most part, have to deal with things that fall into the third category.

Permaculture is not only a design and engineering discipline; its process is also strategic. Simply dismantling the existing governance system and saying to people, ‘it’s up to you now’ would probably be, let’s say, sub-optimal. A pincer movement is more strategic. Encouraging the development of adapted-to-local-context governance systems in all local communities and thus making them ready and capable to take on the new responsibilities.

Mollison was convinced that local governance is more efficient and can, and should be, more just. He was also convinced that local production for local needs, as far as possible, is also the way to continue going. These are both ideas that have motivated the following generations of Permaculture designers.

The Bioregional movement preceded Mollison’s book, but, as with anything worthwhile, he included it as a strategic and potentially effective way to organise our governance systems. Put together, we have 90%, or so, of important decisions are taken at a local community level, let’s say 8% are taken at a bioregional level, and the rest at a national level. The decisions at the national level are discussed and decided at the local and bioregional level and then coordinated to find the best possible and most effective consensus among these decisions. Responsibility returns to people, and the expensive, political elites who run today’s dysfunctional governments disappear.

So far, we have explored the people part of ‘A beneficial authority returns function and responsibility to life and people’. Something that can be confusing is understanding what is meant by ‘giving function and responsibility back to ‘life’. Let’s take another agricultural example.

In the 19th century, soil fertility was maintained by recycling animal waste and importing guano. The sources of the latter were starting to run dry, so governments appealed to chemists to find a solution. Chemists deal with atoms, molecules, and suchlike; they didn’t concern themselves with living processes. A chemist came up with an industrial process to fix nitrogen from the air. We still use the same process, and it is highly energy-intensive. The ‘function and responsibility’ for maintaining fertility fell to an artificial process. Had the same governments appealed to biologists, then the story would have been different. They would have given the ‘function and responsibility’ to life and life processes. They would have pointed out that plenty of living species naturally fix nitrogen from the air. They would have promoted a different form of agriculture. One which emphasises cycling animal and human waste to crop fields, co-cropping the main crop with nitrogen-fixing ones. They may have even gone so far as proposing agroforestry-type systems.

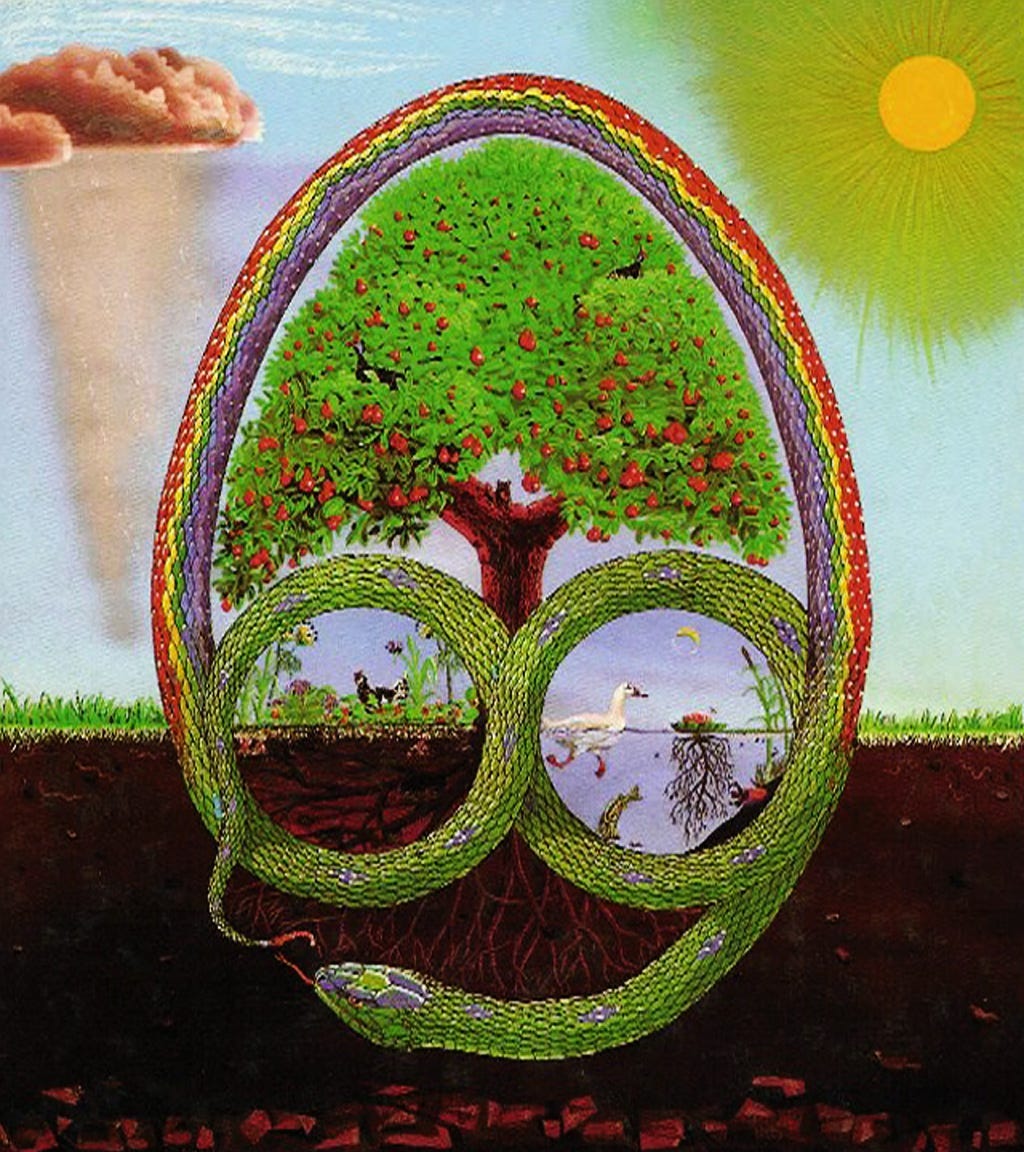

Life itself remains a mystery; we know quite a lot about what it does and how it works, but we don’t know what it is. We know that living organisms have been around a lot longer than we humans, and we know that living organisms organise themselves in complex ecosystems. These are adapted to the local contexts and co-evolve with them. Ecology as a scientific discipline could be defined as one that seeks to understand how living organisms organise themselves. We are living organisms, and we live within ecosystems. In fact, each one of us is an ecosystem made up of human bacteria, fungi, viruses, bacteriophages, etc. Permaculture is based on, amongst other things, scientific ecology. Designers study ecosystems and seek to adapt their organising principles to the human world. This means that instead of looking to philosophers and political scientists, they look towards life and how it thrives, adapts, and self-organises. Again, we find ourselves giving ‘function and responsibility’ to life, in this case as a guide to how we can best organise our systems. We want the latter to be circular, creative, abundant, and resilient, all of which are characteristics of most ecosystems we know about.

That said, as behaviorally modern humans, we have been around for quite a while, for at least around 50,000 years or so. This means that a Permaculture designer has to understand not only the ‘human animal’ itself, but also a whole range of cultural and individual differences. Humans, over the last few millennia, have developed socioeconomic systems that are not only profoundly harmful to the biosphere in which they function but to people themselves. We poison ourselves with a variety of synthetic molecules, pollution, and ultra-transformed foods; we poison the air we breathe and the water we drink. These systems care neither for the Earth nor people. This is the opposite of what Permaculture designers seek to do. Their objective, on a big scale, is to find ways to create human societies that mimic the ecosystems around us and that integrate harmoniously with them. At a smaller scale, it’s the same thing with a farm, market garden, small-scale industry, a village, or an urban neighbourhood. These will incorporate individual and cultural differences. Diversity is valued as something that can help us create resilient and equitable societies.

Anger is an energy; it can be a positive one. The fact that even today, there are millions of people in food and fuel poverty, who live in shoddy, mouldy housing, whose lives are cut short by pollution, and whose living conditions should make us angry. The same is true of the obscene environmental destruction and beauty being trampled to make disposable consumer goods, often by low-paid or child labour. The further fact that our ‘leaders’ will not do what is necessary to deal with our multiple crises should make us very angry.

The design and engineering discipline that is Permaculture offers us a channel for this. Permaculture designers know that we have, ready to hand, all the solutions, technical, social, agricultural, etc, that we need. As Mollison pointed out, ‘they are embarrassingly simple’.

The Permacultural vision

Redesign and then strategically implement these designs to transition our systems to ones which care for the Earth and people. These systems are inherently fair, equitable and ecological (in its modern sense).

The Permacultural mission is threefold:

Act to protect and preserve natural ecosystems that still exist.

Repair and extend damaged natural ecosystems

Design and build human systems that care for the Earth and people, and fit harmoniously into the biosphere.

There is nothing ‘inevitable’ about poverty, poor housing, destructive industry, and agriculture. Nor injustice, inequity, war and conflict. The are emergent characteristics of yesterday’s and today’s dysfunctional socioeconomic systems. Changing the characteristics of a soil will mean different plants will grow. Transitioning our systems away from their current trajectory means the toxic byproducts that are the cause of so much misery and waste will disappear.

We have a vision and a mission. We also have the design and engineering discipline that can make both a reality. We have the tool, it’s up to us to use it. For us, our children and our children’s children and the biosphere itself.

It is noteworthy how permaculture for many has been reduced by many to either a set of techniques, or a strategy for self survival, the danger is of losing the big picture, planetary survival!

Had to sit on my comment and allow it to 'think' for awhile, esp over the last 5 years experience. We've had a blessing, now ending this year. In 2020 we invited a 34 ft, white school, 'work' bus (really tricked out with a kitchen, shower, bedroom area and TV too) to park in the driveway. Our "homeless" couple lived with us 'on the property' and exchanged odd jobs in lieu of any rent while learning Permaculture design .

If the above sounds slightly 'off radar', it had to be. Our city ordinances are very limiting and any nuisances are swiftly complained about. These then 25 year olds were a new wrinkle which required cultivation and good strategy to slide into the culture of urban retirees and stable professional careers(IOWs potential NIMBYs). We literally could NOT 'poke the bear' since we had law enforcement in 3 homes around the entrance.

I prepped my cul de sac neighbors one month earlier with a number of discussions:

a.first to test for any negativity. They'd been fed a previous 5 year diet of 'egg gifts' and were offered 'help' with their own 'work needs'. Chicken eggs are such 'gateway drugs'.

b. Soothing concerns of most things you can guess about.

and etc.

I learnt a long time ago that Social Capital needs building before Political Will can change. Ratio of 10 to 1 in most any detail listing potential concerns still applies.

In my uncertified opinion, Time is Permaculture's greatest tool. Using time proves our visions and concepts. It allows us to change processes fait accompli but causes resentment much like 'prepping', 'homesteading', and other movements have done when the bounty of intellectual capital is perceived to venture into capitalism.

Permaculture is a human right much like health care. And Designers(or students), like Nurses are expected to be overly altruistic. Their services are expected to be generous and come from the commons.

I can't articulate your kind of astuteness and am so very glad you are puzzling everything out.

Thank you.

Oh, and the kids? They were gifted a mostly paid apartment from an ailing relative. They are their own property owners now. Bittersweet indeed.